The making of my Shakuhachi

step by step

Taketori – Harvesting

Every winter is the time when I harvest my bamboo for Shakuhachi making. This is done according to the moon, when the sap is down in different bamboo groves in France.

I’ve also been harvesting bamboo when travelling in other countries.

I love this time for connexion to the plant and the atmosphere inside the grove. It is very rare in instrument making to be able to harvest your own material.

The botanical knowledge on bamboo is important to collect the best matured culms that would give the most resonant fibre.

Each piece has to be at least 4 or 5 years old and having grown in the right conditions (not to wet and rich soil in order to have a denser fibre).

In Japan, mountainous bamboo is considered to be the best suitable for crafting.

The specificity of bamboo for Shakuhachi is that it is harvested with its root part which you need to dig out from the ground; a pretty tough and careful work were you have to avoid damaging the bamboo while pulling it strongly.

It is rather difficult to fine the perfect pieces which would have the right diameter, nodes proportion and characteristics to be turned into a good Shakuhachi.

Process of curing Bamboo

The curing treatments applied after harvest are essential to obtain a wood with the good acoustical properties and also to avoid number of splitting culms when drying.

Several methods are used by bamboo harvesters. It is not possible in my opinion to claim that one is the best insofar as they give different results on each bamboo species.

It is an experimentation work on it specific to each maker.

Amongst those methods, you can find heating or steaming, sun curing, soaking in river or in brine (salted water), smoking…

The traditional Japanese methods consist of Aburanuki (lit. “removing oil”) heating over charcoal right after harvest and sun curing for a few weeks before years of drying in a cool place.

I’ve been experiencing every year different combination of these techniques.

The whole process of curing and drying my bamboos is taking 3 to 5 years.

Preparing Bamboo for Shakuhachi making

The first step on the bamboo consists of hollowing it by opening all the internal nodes (they are not completely opened since irregularities in the bore also give its acoustical singularity).

The foot part with roots is plain and requires opening with hand borers and shaping with rasps.

The roots are removed and the foot is shaped; this root-ended part of the Shakuhachi is for me like his face, its aesthetics expresses the character of the bamboo. (some are nicely finished, other are odd or completely shaved…!)

A lot of time is given to observe and measure the bamboo, its general shape, its diameter, the repartition of its nodes in order to determine what is the best shakuhachi that this particular bamboo can be turned into; the tonality of the flute, if it will be in one or two parts…

Now the air column is ready, it needs a resonator to be set in vibration…

Utaguchi – The embouchure

In order to create a sound in a flute, it needs a resonator that is what is going to turn a stream of air into a soundwave inside the air column (the tube).

In a word, what turns breath into sound

With Shakuhachi, the embouchure consists of a notch in the bamboo creating a sharp bevel usually strengthened with an inlay made of horn, ivory, bone or synthetic materials.

Inserting this piece into the blowing edge is a very meticulous work.

Its shape determines the lineage of the maker (Kinko : triangular, Tozan : rounded).

Once this step is fulfilled, we can get a first sound.

This is called the fundamental tone which is determined by the overall length of the tube.

Thus, we have to tune this tone to give the keynote of the flute we can adjust it by either shortening the length by cutting part of the rooted foot (but we still want to keep some of it) or the opening bell in the end.

The last option when the size of the flute is not corresponding to the tonality we want, it is possible to make the flute in two parts (nakatsuki-kan) and remove from the middle on portion of the tube.

This is much more complex because the nakatsuki joint will have to be perfectly fitted to give back its sound to the flute.

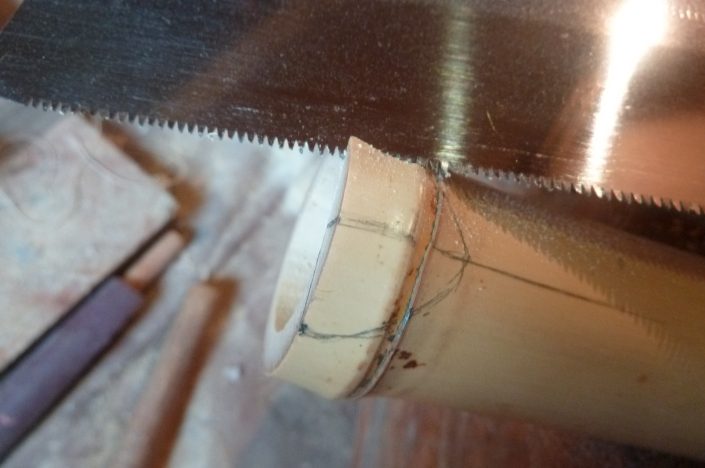

Nakatsuki – The middle joint

It is rather rare to find a piece of bamboo with the exact proportions to suit to a desire tonality (length) and the possibility of placing both embouchure (on a node) and tone holes (between nodes).

That’s the reason why most of the modern Shakuhachi are made in two parts assembled with a mortise-type of joint called Nakatsuki entirely made from bamboo. This enables to adjust the length of the flute very precisely and also to work more comfortably on the bore by dividing its size in two.

Nobe kan : Shakuhachi in one piece of bamboo

Nakatsuki kan : Shakuhachi in two parts

This joint is realised in the middle of the flute, between the third and fourth tone hole.

This part of the bamboo is then weakened and needs to be reinforced with bindings or metal rings. The sealing of the joint is made by several coats of strong Urushi lacquer.

Almost all Ji-ari types of Shakuhachi are made in two parts.

Almost all Ji-nashi types of Shakuhachi are made in one piece.

Tuning

The tuning process in Shakuhachi making is done in two parts :

Tone holes placement

The five holes are placed following calculations in regard of the length and diameter of the bore. They are first drilled small and then progressively opened to until they reach the correct pitch.

We can adjust the harmonics between first and second octave by enlarging the hole either to the top or the bottom of the flute.

With luck (and a good selection of the bamboo), the natural shape of the bore will give a well balanced acoustical result in pitch, stability of tone, timbre and volume but this is rather rare !

Most of the flutes will need bore adjustments to fine tune them into well balanced playable instrument.

This process is delicate and time-consuming; it requires knowledge and experience and a lot of patience !

Tuning the bore of the Shakuhachi

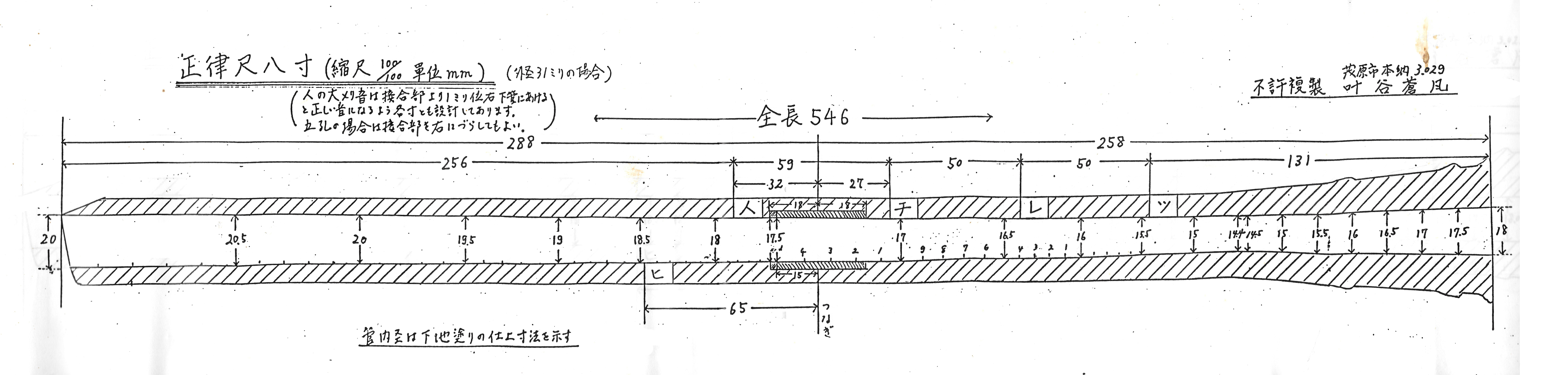

The proportions of the bore in the Shakuhachi is pretty close to those of the recorder flute

i.e. from the embouchure, the tube is relatively cylindrical the a reversed cone until a precise point where it widens again to the end.

These parameters are essential in the acoustical consistency of each instrument they are what gives each flute its ‘soundprint’.

When the natural shape of the bamboo is not corresponding, it needs to be modified by removing or adding material at precise points of air pressure affecting directly the harmonics of each note.

From that, two different approaches :

- With Ji-nashi, this fine tuning of the bore is only done by widening slowly the bore to get a good bore profile keeping it as natural as possible.

(In the case of Ji-mori, just some spots of Ji are added at resonance points) - With Ji-ari, the whole bore is designed with Ji plaster (mix of clay, water and urushi lacquer) to fit to specific measurements. This is usually controlled by the use of gauges.

The Ji is applied in many layers needing few days of drying successively sanded to slowly give its shape to the bore. It is a long process to completely re-design the bore.

During the whole tuning process, the Shakuhachi is played intensively in order to evaluate its overall improvement and sound-checking each note. A good knowledge of the playing techniques of the instruments is essential to master this art of tuning.

I sometimes have to let a flute beside when I can’t manage to solve an acoustical issue waiting weeks or month for an understanding that might come with another flute and give me the intuition needed to improve…

When the maker is globally satisfied with the instrument, it is then time to lacquer the bore.

Urushi lacquer

Lacquering the bore of a Shakuhachi (or even as in ancient time the outside) protects it from moisture, mould it also hardens it an improve considerably tone colour (enhancing high harmonics) and the general response of the flute.

The Japanese Urushi lacquer is purely vegetal, extracted fram the sap of the ‘lacquer tree’ (Rhus vernicifera) it hardens and last in time as no industrial modern lacquer can do.

(The oldest Chinese lacquerware discovered is about 3000 years !)

Applied in several layers successively polished, it becomes extremely strong and waterproof.

Urushi is polymerizing (hardening) with heat and humidity. The freshly lacquered Shakuhachi are to be placed in a steam box (Furo lit. ‘bath’ in Japanese) each layer needs almost a week to completely cure.

Different types of lacquer are used at each step; the row Seshime urushi, transparent, coloured with pigment and filtered (in black or red)…

I started working with Urushi in 2017; it’s almost a new craftsmanship that I have to learn now !

It’s important to know that some persons can get skin allergic reactions from light to severe to the Urushiol (the main molecule of Urushi). Except in rare case of high sensitivity, these reactions only occurs with fresh Urushi. Normally, when properly cured, there aren’t any residual Urushiol in the Shakuhachi.

From the first sign of skin reaction, it’s important to carefully wash hands and mouth with soap and the bore of the flute also.

Bindings

The bindings are used to prevent or repair splits and cracks in the bamboo which is still even after decades a living material reacting to changes of weather conditions.

To repair

Generally, bindings are made on a shakuhachi only for repairing cracks; they can be done with different materials and techniques.

According to the wabi-sabi sense of aesthetic, a properly repaired flute is ennobled by these traces of time passing reminding us the impermanence of life.

Some of the old flutes from top makers are completely bound by different repairs in time; this tells about the story of the flute.

To prevent

The nakatsuki joint of two parts shakuhachi is always bound because more sensible to crack after repetitive use. Those bindings are inlaid in the skin of the bamboo, sealed with urushi and finished with a fine thread of rattan.

This traditional technique is very meticulous and time consuming.

On the straight bamboo Shakuhachi (meditation and student models), I always put several preventive bindings.